Writing

awards | publications | book reviews

Reviews published in M/C Reviews:

Culture and the Media

A Time to Speak: The Politics of Suffering: Indigenous Australia and the end of the liberal consensus by Peter Sutton

Writers for this website have the privilege of reviewing only the books they wish to review. The Politics of Suffering was not a book I wished to review. Fearing the distress which the grimness of its content might cause, I regularly passed over it each time it came up for offer. Unfortunately these feelings must have been shared by my fellow reviewers because week after week the ominous title re-appeared on the review list. When I googled the internet I saw that Avid Reader Bookshop was still calling plaintively for reader reviews but apart from that all I could find was a carping attack by an American academic. (By now, of course, there are others.) At last, driven by conscience, I requested a copy. I’m here to tell you that I need not have procrastinated. There is nothing to be afraid of and much to be gained from the pages of this book with its black cover and accusing (or is it beseeching?) eye.

Knowledge, after all, is empowering. When nothing seems to work and you don’t know why, you become confused and feel powerless. Moreover, in presenting the facts the author, anthropologist Peter Sutton never indulges in the kind of lurid sensationalism favoured by the media when describing the violence and mayhem endured by members of Indigenous communities. His latest book is more concerned with unravelling the complex web of misunderstandings, omissions and downright lies that bedevil our understanding of the conditions under which Indigenous people live. Professor Sutton writes because he is motivated by a belief in a fair go and because he is uniquely positioned by the knowledge of a lifetime to promote it. He writes to provide the wider (whiter) community with a more informed account of what is going on than they will find in the media or in government policy statements.

The Politics of Suffering is a heartfelt but sober documentation of the sad recent history of governmental and other white interventions (or lack of them) in Aboriginal affairs. There has been too much cultural blindness says Sutton, too much ineptitude and ignorance – both benign and malign - informing state and federal policies and too much denial of dysfunction in Aboriginal communities by white liberal supporters. The cost of such ignorance and silence is too high to be tolerated.

There is too much bureaucratic jargon about ‘Indigenous disadvantage’ which merely papers over grim reality. ‘A murdered mother is not ‘disadvantaged’ - she has lost her life.’ (76) Too much well-meaning white liberal defence of Indigenous communities on the grounds that violence is common to all communities. Of course it is. What is different and alarming as we now know, is the prevalence of such violence. Too much ‘blame the victim’ syndrome on one side of the political spectrum and on the other, too much denial of the terrible things that are happening. As Sutton points out, ‘courting the danger of offering more cannon fodder to the blamers is as nothing compared to the dangerous world into which Aboriginal infants have leapt every day.’ (85) Too much dishonesty or at best omission in government reports. It is time, says Sutton, to put in place sanctions that enforce honesty. Sincerity is not enough. (79) Too many bureaucratic inquiries that fail to take into account the tragic interplay between Indigenous cultural traditions and government interventions. Too much ‘yabber’ and not enough reality. (83)

The reality, as Sutton makes clear, is far worse than it ever was. The introduction of state-sanctioned alcohol to Indigenous communities has much to do with this but cannot provide the whole answer. Alcohol has always been available to urban Aboriginals yet the levels of sexual violence and murder in the cities are nowhere near those found in remote communities. Nor can blame simply be laid at the door of the culturally destructive and often vicious policies of missionaries and government superintendents. According to Sutton, some of the worst cases of social breakdown occur in communities that remained relatively unscathed by the inroads of white authority.

Today more than ever the answers lie, claims Sutton, in understanding the complex interactions between traditional cultural practices and the various measures that governments have put in place based on their own cultural values. In the late 60’s, for example, official government policy encouraged the introduction of ‘wet canteens’ with takeaway quotas. This accorded with white values as Indigenous academic Marcia Langton learned on a visit to Palm Island. She was told by a staff member that alcohol would encourage the work ethic: warm beer would lead to the need to earn enough for a fridge. (v) The results of this policy were catastrophic. When you put freely available alcohol in the context of an under-employed self-managed society in which many of the old protocols for controlling behaviour have been broken down by missionaries and government superintendents of reserves but the traditional authority of senior males to use physical chastisement has not, you have a recipe for disaster on a huge scale.

The ‘code of silence’ of anthropologists and other well meaning whitefellas from the 1970s onwards certainly has not helped matters either. Sutton began his career as an anthropologist in the early Seventies and was part of the progressive politics of that era (as I was.) It was in these more radical, hopeful years that huge advances in Aboriginal rights were made: improved infant mortality and longevity rates; the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975; the first achievements in land rights reform. In those days it all seemed so simple. We rightly (I still believe) championed the entitlement of Aboriginal people to preserve their culture and wrongly (I now realise) refused to accept that there were problems, little realising that we were thus forming an unholy alliance with racist or ignorant government policies. It is time, as Marcia Langton says in her introduction, to open our eyes to reality and place the emphasis not on the right to be different but on the right to be free from violence, neglect, ignorance and corruption.

Though The Politics of Suffering is not written in an unduly harrowing style it nevertheless deals with matters that make uncomfortable reading for those of us who care about the rights of Indigenous people but are confused about the way forward. Perhaps that’s the real reason I didn’t want to review this book. I’m glad I did. I now have a better understanding about so many of the issues involved (and also a better chance of winning arguments with racists). I now know, for instance, that there are more reasons for overcrowding in Indigenous homes than can be explained by inadequate and/or mismanaged government funding, though this must remain the major factor. Such as the persistence of kinship groups who traditionally would have bedded down together on cold desert nights beside the warmth of a campfire, and, more chillingly, such as the new need to have safety in numbers against night invasions.

Sutton’s purpose in writing this book was to emphasize the damage caused by ‘the code of silence’ observed by many white liberal supporters in recent decades. It is a pity that in doing so he downplays the far more damaging impact of the destructive policies of missionaries and successive governments. It is these policies more than any liberal consensus that have contributed to the self-harming behaviour of a people raised in self-hatred under conditions of Apartheid-style institutionalised powerlessness. Putting aside this surprising flaw in the writing of a man who has devoted a large part of his life to improving the lives of Aboriginal people, The Politics of Suffering nevertheless remains a valuable contribution to the current debate about the causes of in-turned violence in remote communities. As Professor Langton says in her introduction, Sutton’s book can only increase understanding which in turn will help save the lives of many Australians. For some reason, as I type these words, I’m hearing a line from a song on an old CAAMA (Central Australian Aboriginal Music Association) CD called ‘From the Bush’. In the breathy, grainy voice of the desert people, a young man is softly and gently intoning:

‘I’m a ma-a-an, just like you.’

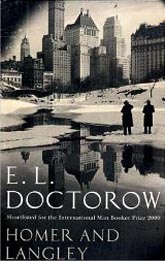

My God, it’s the Collyers: Homer and Langley By EL Doctorow

Barak Obama recently disclosed that E.L. Doctorow is his favourite contemporary author. Perhaps the U.S.A. president is drawn to Doctorow’s choice of subject matter (America’s radical past) though of course there could be other reasons why this writer’s novels might appeal to a man who is no mean story-teller himself - their beautifully crafted language, for instance, or their commitment to truth-telling. But if you want to discover for yourself what Obama finds to admire in this American novelist, you could do no better than read his most recent book, Homer and Langley.

Homer and Langley fictionalises the lives of two real life brothers, Homer and Langley Collyer, who were born in New York at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Collyers’ eccentric behaviour captured the imagination of their fellow Americans during their own lifetime but Doctorow felt that the truth needed to be reclaimed on behalf of two reclusive but harmless men in the face of their increasing demonization by the media. In Doctorow’s novels no-one is ever simply the Other, no-one is without his own compelling story, which may be another aspect of Doctorow’s writing that Obama appreciates. A kind of outsider himself, he may like the way Doctorow humanises those members of society designated as outsiders or outcasts.

Born in New York of Russian-Jewish parents, Doctorow grew up knowing about the Collyer brothers. In an interview with Sarah Crown he remembered: ‘I wasn’t the only teenager whose mother looked into his room and said “My God, it’s the Collyers.” ’ (Guardian 2010). Yes, Homer and Langley lived in mess. They were hoarders, but not just any old hoarders. They were hoarders on a grand scale. Over the years the pathways through their large upper middle-class home shrank beneath mountainous piles of accumulated junk. At the end of their lives they were found buried, literally, beneath an avalanche of debris. Or at least that was the fate of the elder brother, the possibly pathological Langley. His blind and by now deaf brother Homer then starved to death for want of assistance.

Homer and Langley doesn’t set out to provide a factual biography or even a psychological explanation of what lead to this bizarre fate. Its aim is larger, to do justice to the truth of two damaged men who only did harm to themselves. And just as importantly, to tell their story as a kind of metaphor of American society during the same historical period. Because, though never spelt out, it is impossible to read this novel and not be struck by the parallels between the brothers’ lives and the society in which they lived. On one level at least, Homer and Langley can be read as a Biblical-style parable of the increasing acquisitiveness and individualism (in its best and worst senses) of modern America. Doctorow’s comment about a previous novel to the effect that it wasn’t so much about the main characters as about the state of their country’s mind, could also be made about Homer and Langley.

In his interview with Sarah Crown for the Guardian, Doctorow said of this novel: ‘I found myself writing this line: I’m Homer, the blind brother.’ He had found the voice and from then on, he says, the book began to write itself. Some critics have complained that there is not enough going on, not enough dramatic action. But these readers may be missing the point, which for me at least is the compelling voice of the younger brother. The voice of Homer is as much an achievement as the voice of Ned Kelly in Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang or the voice of Grace in Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace. Deaf and blind, Homer becomes, through the medium of his Braille typewriter, the innocently perceptive witness to his own life as well as to the larger social and political life of his times.

Though Homer and Langley contains no love interest in the traditional romantic sense, what gives this book its heart and centre is the story of the love between two brothers. The Collyers always care for and try to protect one another even if their methods are sometimes a trifle eccentric. Langley the elder has returned from the Great War in a state of physical and mental trauma from which he is never to recover. He rejoins his wealthy parents and blind brother in their brownstone mansion but in less than a year the brothers are orphaned when their parents die in the influenza epidemic of 1918. Left with the servants in their parents’ multi-storeyed house, the brothers must find ways of coping with their different afflictions and making meaning out of their lives.

Over the years as the servants depart and Langley begins to fill the house with junk, they entertain people to tea-dances, are visited by prostitutes, held hostage by gangsters, give sanctuary to flower power Hippies and fight valiant, foolish battles against the municipal postal, electric and gas services. But as Langley nails up the shutters forever, the two brothers come to depend more and more on each other for mental and physical sustenance. Towards the end of their lives, Homer reflects on the children who have taken to throwing stones against their shuttered windows:

‘Children are the carriers of unholy superstition, and in the minds of the juvenile delinquents who’d begun to pelt our house Langley and I were not the eccentric recluses of a once well-to-do family as described in the press: we had metamorphosed, we were the ghosts who haunted the house we had once lived in. Not able to see myself or hear my own footsteps, I was coming around to the same idea.’ (198)

Doctorow’s novels are chameleon in style. Each takes on the form and diction suited to its subject. In this latest work, the blind brother Homer speaks to us with the sometimes old-fashioned but always precise language of a man whose outlook has been formed in a more innocent world than ours, a world that knew nothing of moon walks or nuclear bombs. In its plot outline, the story of two apparently wasted lives does not seem very edifying. What makes this book so appealing is its elegantly spare and flowing language and the way that language fits seamlessly with meaning, whether overt or in the subtle layers of sub-text. Homer and Langley has justly been claimed to rank amongst the very best of E.L. Doctorow’s novels and if you haven’t read this author before, then his latest book is a good place to start.

Murderesses, Conwomen and Nymphomaniacs - Angela Carter’s Book of Wayward Girls and Wicked Women

In today’s climate of internet imperialism when even an august journal such as Meanjin can disappear overnight as a physical object, it behoves those who publish books to ensure that their products are as seductive as possible. During her time as Meanjin’s editor, Sophie Cunningham presided over a high standard of design which became part of the pleasure of reading her journal, but it is difficult to see how the incoming editor will be able to ensure the same degree of enjoyment online. As more and more books and journals disappear into virtual reality, it is clear that if publishers wish us to buy their products in the future they must look to their strengths. The books they market will need to be covetable objects, shapely in the hand and easy on the eye. A recently re-issued anthology of short stories, Angela Carter’s Book of Wayward Girls and Wicked Women is a model in this regard. With its witty, stylish cover, its elegant deployment of fonts, its scarlet ribbon bookmark and its nostalgic scent of good paper, it is the sort of book that enhances the enjoyment of reading, the sort of book you will want to keep on your shelves and take down every now and then for dipping into.

The contents are equally beguiling. Angela Carter, who died in 1992, has put together an anthology of short fiction drawn from authors across the globe. Some are novella in length, others no more than a few pages but all the better for that; some are contemporary while others are by writers with their roots in the nineteenth century; all are written by women; all are united in finding their subject matter in that perennial chestnut - female perversity.

In her introduction Angela Carter comments that the protagonists in each of the stories selected are presented as ‘perfectly normal’. In the hands of male authors, she suggests, the same characters would become: ‘predatory, drunken hags; confidence tricksters; monstrously precocious children; liars and cheats; promiscuous heartbreakers.’ (vii) Women writers, Carter claims, are kinder to women. (I would add ‘tend to be’ but Carter has never been one to deal in shades of grey.) Only one story deals with female sexual destructiveness, her own ‘The Loves of Lady Purple.’ But as she points out, Lady Purple is not real. She is a puppet whose character has been fabricated by a male puppeteer and in vintage moralistic Carter style, is subsequently allowed to take her vengeance upon the man responsible for her distorted persona.

Angela Carter’s Book of Wayward Girls and Wicked Women is full of discoveries. The editor’s wide ranging selection based on her own extensive reading means that there are more surprises than are usually found in anthologies, making this book a Lucky Dip rather than the more predictable Christmas stocking of goodies. Did you know, for instance, that George Egerton (alias Mary Chavelita Dunne) is Australian? I did not or if I did I had forgotten. Her contribution ‘Wedlock’ is perhaps the most powerful in the collection and was taken from her volume of short stories Keynotes published in 1893. It is a harrowing and finally shocking tale, entirely empathetic and believable, anchored firmly in realistic working class dialogue.

Another writer, Elizabeth Jolley, born in England but one we also like to claim as Australian, provides the lead story in the collection. ‘The Last Crop’ is Jolley at her scintillating best. Has she ever written anything better, I wonder? Jolley’s cleaning lady heroine, known simply as Mother (the tale is told by her daughter) is the most full-blooded, devious, good-hearted conwoman ever to enliven the pages of fiction and the dishonest way in which she finally solves her family’s problems seems somehow only right even while it leaves you gasping.

Disappointments, if they exist at all, are few and far between in this anthology. Even allowing for vagaries of taste, it’s a fair bet that readers will enjoy most if not all of the stories Carter has selected. There are plenty to choose from: Jane Bowle’s slyly comic tale of an American in Guatemala; Leonora Carrington’s surreal piece of absurdism titled ‘The Debutante’; Vernon Lee’s atmospheric gothic story of the mysterious Mrs. Oke; Jamaica Kincaid’s succinct list of warnings designed to feminise a young girl; and one of my favourites, Djuna Barnes’ Tolstoyan peasant tragedy that surprises with a happy ending. I would read it again and again just for her wicked turn of phrase. Probably I will do so in the slow days after Christmas, when the sight of that elegant Beardsley-style cover tempts me to take the Book of Wayward Girls and Wicked Women down from the shelf and open its creamy pages again.